Ethnic Minorities and the State in Eurasia

(2009-2016)

Senior Researchers: Patrice Ladwig, Sayana Namsaraeva, Oliver Tappe

Associates: Dorothea Heuschert-Laage, Chia Ning

Doctoral students: Elisa Kohl-Garrity, Elzyata Kuberlinova, Simon Schlegel, Fan Zhang

The project 'Ethnic Minorities and the State in Eurasia' was launched in 2009 and concluded in 2016.

Subprojects

Heuschert-Laage, Dorothea (2011-2014):

a) The Lifanyuan’s Scope of Responsibility over Mongolian Legal Matters in the Qing Dynasty

b) Restricting Pastoral Mobility: the territorial integration of Mongols into the Qing Empire

Kohl-Garrity, Elisa (2012-):

Forms of Respect and Disregard in Mongolian Culture [Dissertation project]

Elzyata Kuberlinova (2014-):

Religion and Empire: Kalmyk Buddhism in Late Tsarist Russia [Dissertation project]

Ladwig, Patrice (2009-2014):

Buddhist Statecraft and the Politics of Ethnicity in Laos: Buddhification and interethnic relations in historical and anthropological perspective

Namsaraeva, Sayana (2010-2011):

a) Ritualizing Imperial Authority in the PRC: exploiting of Qing dynasty imperial rituals to legitimate Chinese Communists authority over the Buddhists [Publication project]

b) International Workshop “Administrative and Colonial Practices in Qing Ruled China: Lifanyuan and Libu revisited” [Preparatory project]

Ning, Chia (2011-2014):

a) Lifanyuan and Libu: institutional developments and agencies in Qing China

b) The Population in Nationality Categories and Their Institutional Affiliations in the Qing World

Schlegel, Simon (2011-2016):

How to Maintain Ethnic Boundaries: past and present mechanisms of ethnic distinction in southern Bessarabia [Dissertation project]

Schorkowitz, Dittmar (2009-2016):

Dealing with Nationalities in Eurasia: how Russian and Chinese agencies managed ethnic diversity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries

Tappe, Oliver (2009-2014):

Reconfigurations of the Past in an Ambiguous Present: memory discourses, social change and inter-ethnic relations in Houaphan, Lao PDR

Zhang, Fan (2011-2016):

Manjusri’s Gift: the establishment of Qing imperial order in Tibet, 1652-1793 [Dissertation project]

Ethnic Minorities and the State in Eurasia (EMSE) was created as a focus group of the Department’s newly established research group for Historical Anthropology in Eurasia following the appointment of Dittmar Schorkowitz as a research group leader (W2 position) in 2009. Conceived as a research framework for historically minded anthropologists, the new focus group investigated the histories of ethnic minorities and their varying experiences with the state in different times and places. EMSE started with a three-part pilot study that explored relations between ethnic minorities and the state in different areas in Europe and Asia; this was supplemented during the course of the project through collaborations with additional scholars. A common element in each of the case studies was an interest in minority policies and the cross-epochal importance of various agencies (such as Buddhism, collective memory, and governmental institutions) for the integration strategies used by multi-national states. The projects by Patrice Ladwig and Oliver Tappe covered partly overlapping areas of Southeast Asia, while Dittmar Schorkowitz focused on Russia and China. The group entered its pre-final phase in 2014 with the completion of four sub-projects (Dorothea Heuschert-Laage, Patrice Ladwig, Chia Ning, Oliver Tappe) and came to a close with the publication of the Lifanyuan volume by Dittmar Schorkowitz and Chia Ning and the successful completion of Simon Schlegel’s doctoral thesis in 2016. Fan Zhang left the group the same year with her dissertation unfinished, to continue her studies at the University of Leipzig.

The idea for a new research group for historical anthropology in Eurasia was much informed by concerns about anthropologists’ heavy focus on ethnography to the point of neglecting other methods; this trend, which has developed over the last century, is particularly prominent in Anglophone traditions. While not exclusively synchronic, ethnographic approaches have emphasised relatively shallow temporalities that seldom extend back beyond the reach of the memory of elderly informants. Although this presentist focus has been productive in many areas of research, the potential of longue durée approaches remains undiminished, not least for understanding how contemporary diversity results from past processes (cf. Schorkowitz 2012a, 2015). For most of the twentieth century, and particularly during the Cold War, it was difficult for Western anthropologists to conduct studies – whether synchronic or diachronic – in Russia and China, Laos and Vietnam. The removal of many of these impediments to access in post-socialist times enabled the focus group to develop new research agendas for historical anthropologists in these parts of the world, including extensive fieldwork and archival research.

Among the basic goals of EMSE, and in particular my own sub-project, was to move beyond postcolonial debates on ontologies and cultural turns in favour of an empirical contribution to the anthropology of colonialism based on historical and social analysis and basic research. Consequently EMSE’s research questions were related to different forms of colonialism (internal, continental, and overseas), to nation states and the cross-epochal legacies of imperial formations, to different types of integration, frontier regions, and statecraft. Despite the geographical variety of the EMSE projects, the development of the group’s comparative and theoretical focus emphasised shared concepts and methodological concerns. To this end, conferences and workshops were held on topics that included colonial practices and minorities in Qing China, colonialism and mimetic processes worldwide, and archival methods and theory. Thus, what started as three pilot studies on the historical dimensions of state-minority relations in the countries of Laos, Vietnam, and Russia and China, soon turned into a joint framework for comparative investigations.

When we look at the world’s empires historically, certain shared characteristics are clear: they developed lasting strategies to integrate cultural diversity resulting from an immense variety of ethnic minorities they have absorbed in the course of their expansion. They were experienced in managing socio-cultural diversity and created institutions and ministries for dealing with ethnic minorities. The social and cultural worlds of these minorities were subject to continuous transformation via exchange and transfer, communication and administrative acts; these processes were often embedded in hegemonic practices. Imperial formations are not necessarily a thing of the past; they may still be regarded as a cross-epochal, operable variant of governance in Europe, Asia, and beyond, as argued by scholars such as Jane Burbank, Frederick Cooper, Nicola Di Cosmo, Michael Khodarkovsky, Beatrice Forbes Manz, Peter Perdue, and many others. Although the transformation from empire to nation state and the replacement of dynastic bureaucracies by party systems is widely seen as one of the great projects of political modernity, it has not taken place homogeneously nor to the same degree everywhere. As measured by a) the heterogeneity in socio-political structures, ethnic identities, and languages spoken, b) centre-periphery dependencies, and c) unsettled ‘ethnic’ conflicts, the project of nationalising the state is still incomplete in many places, whether in Russia or in China, in Laos or in Vietnam (the latter two states being empires en miniature).

In his project, entitled Buddhist Statecraft and the Politics of Ethnicity in Laos, Patrice Ladwig explored how Buddhism and its notions of statecraft and political technologies of power has been used to mediate the relationships between ethnic minorities in the highlands and Buddhist groups living in the lowlands of Laos. From a historical perspective, Theravada Buddhism, perceived by those in power as a force of civilisation, has been instrumental in the development of a class of religious professionals, permanent and interconnected religious institutions, written culture, and most importantly concepts of kingship, statecraft, and legitimacy. In the wet-rice cultivation areas in the valleys, Buddhism provided the basis for creating taxable supra-village political entities. In contrast, the highlands were populated by numerous and highly diverse animistic ethnic minorities belonging to the Mon-Khmer, Tibeto-Burman, and Tai-Kadai linguistic families. Due to their forms of livelihood, they were extremely mobile and occupied peripheral regions that were mostly out of reach of the early Buddhist states and empires. Using the perspective of an anthropology of the state, the project followed the question of whether and how this statecraft and its practices can be conceptualised as forms of a specific governmentality and internal colonialism that aimed at Buddhifying and civilising groups at the margins of the state, resulting in forms of acculturation and strategies of resistance.

Though exchange and intermarriage between ethnic Lao and the animist Mon-Khmer groups of the surrounding uplands indicates the porousness of religious boundaries, the hegemonic position of the ethnic Lao has also been a constant feature. Buddhist principalities in pre-modern Laos were eager to integrate minority groups not only for economic and military reasons (i.e., slavery and forced recruitment), but also because they considered Theravada Buddhism to be superior to animist belief systems. In order to study forms of internal colonialism prior to the French intervention of 1893, Ladwig analysed Buddhist historiography, local chronicles, and oral histories in which Mon-Khmer groups are classified as forest people who live in a state of savagery without any form of writing or state structure, perform buffalo sacrifices, and are ignorant of the teachings of the Buddha. The sources also emphasise, however, the potential of Buddhist polities to integrate these minorities via conversion, a practice which started as early as the seventeenth century, when residents of Cheng villages were granted a status as ‘temple serfs’, and has continued into the present through the state’s policy of linking Buddhist temples to the new idea of a ‘civilised modernity’. Buddhification as a strategy of integrating ethnic-cultural diversity thus shows great continuity not only from the pre-colonial to the colonial period, but also into the era of the post-socialist nation state.

Insights from theoretical discussions on materiality and political theology were applied to anthropology in order to investigate the crucial role of Buddhist relics in Buddhist statecraft from the pre-colonial era to the present period. The project showed that the reconstruction, erection, and worship of relic shrines can be understood as a process of Buddhification of the state and its territory and population. Archival research and the preliminary analysis of chronicles from Laos and Thailand attested to significant shifts in the religious-political imaginary concerning relics and statecraft over the period that spans French colonialism, the communist revolution and the construction of the Lao nation state. However, there are also continuities to be found: both French colonial powers and the Lao state promoted relic cults and presented Buddhism as a civilising force. Parallels in Burma and Thailand suggest the fruitfulness of this line of research for comparative studies of mainland Southeast Asia.

The project of Oliver Tappe, entitled Reconfiguring the Past in a Lao-Vietnamese Border Region, also looked at Laos, but with a focus on Huaphan, a province located in the mountainous north-eastern part of Laos (adjacent to Vietnam) with a heterogeneous population consisting of twenty-two ethnic groups from four main language families (Tai-Kadai, Mon-Khmer, Hmong-Mien, and Tibeto-Burman). This highland population at the margins of what today are the nation states of Laos and Vietnam was subject to an increasing amount of external interference in local political and economic organisation after the arrival of French colonial powers in the late nineteenth century, and both post-colonial and socialist nation-building processes further transformed the multi-ethnic social structures of the region. Tappe analysed how multi-ethnic social structures were affected by state politics, specifically colonial taxation schemes, land reform projects, changing property relations, and the recent emergence of a capitalist agricultural economy. The ruptures and continuities fall into four periods: colonialism (1893-1954), contested nation-building (1954-75), orthodox socialism (1975-86), and reformed socialism (since 1986).

Before French colonial involvement in Southeast Asia, Lao and Vietnamese rulers were content with mere indirect control over upland peoples, mainly to guarantee the flow of goods from the mountain forests. In pre-colonial times, Lao rulers maintained tributary and marriage relations with certain groups, while the Vietnamese offered titles and ranks to co-opted upland elites. Some groups, such as the Tai Deng, however, constantly moved and mixed and thus created the kaleidoscopic appearance of this specific upland context which challenged the French colonial gaze at the turn of the twentieth century. While developing integration strategies of its own, the French colonial administration adopted existing lowland ‘imperial’ strategies such as the co-optation of local elites, thereby reinforcing interethnic hierarchies and socio-political tensions. Under French colonialism, ethnic minorities emerged as a distinct social category, namely as upland societies outside the dominant Lao and Vietnamese cultural mainstream. As an internal frontier in French Indochina, the upland regions dividing Laos and Vietnam entered a new stage of political and economic integration. As a consequence, this ethnically heterogeneous region must be considered not as a periphery, but as a zone of contact and exchange, of mutual interpenetration of different cultures, and of mimetic appropriations similar to China’s Inner Asian frontier.

In tackling questions of ethnicity and inter-ethnic relations by focusing on the social and cultural shifts caused by the intrusion of modern state power over last 120 years, this research project employed a historical and social-anthropological perspective to identify present representations and reconfigurations of the local past in the context of official state historiography. Since the support of the various upland ethnic minorities in the Lao-Vietnamese border region played a key role in the Lao and Vietnamese revolutionary struggles, the integration of these groups into national narratives remains a critical issue. An analyses of Viengxay/Houaphan province, a former Lao revolutionary stronghold, reveals the ambiguities of Lao national identity politics, which oscillate between the poles of the socialist ideal of multi-ethnic solidarity and the cultural hegemony of lowland Lao civilisation forces. To explore these ideological tensions from a local point of view, the project examined the perceptions of ethnic minorities and their role in the making of Lao state history and practices such as the construction and cultivation of national lieux de mémoire.

Both Ladwig and Tappe applied diverse approaches and methods of historically informed anthropology, making extensive use of archival research (Paris, Aix-en-Provence, Vientiane) combined with multi-sited fieldwork in village societies of their regions. This emphasis on archival sources entails methodological challenges, since official documents generally represent discourses of domination that often only allow for an indirect view of the colonised. Research results of the two projects have been presented at international conferences in Lisbon, Chicago, Madison, Halle, Göttingen, Berlin, Paris, Kyoto, Nanterre, and Mainz. By spring 2014 both colleagues had completed their projects and left the group. Oliver Tappe joined the prestigious new excellence cluster at the Global South Studies Centre of the University of Cologne, completing his habilitation project which he had started in Halle. Patrice Ladwig was offered visiting professorships in anthropology at the universities of Zürich and Hamburg, and then joined the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity in Göttingen.

Focusing on the historical anthropology of Russia from early Kievan state formation to post-soviet nation-building and based on previous research on nationality politics, the project launched by Dittmar Schorkowitz was intended both to reach out for new horizons and to represent analogous experiences in Europe and Asia. Entitled Dealing with Nationalities in Eurasia: How Russian and Chinese agencies managed ethnic diversity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this project concentrated on the classification of minority groups in the later Romanov and Qing empires and the consequences of these majority-minority dynamics for minority policies in the twentieth-century socialist states that succeeded these empires. This rather broad research agenda soon narrowed its focus to the governmental institutions set up to regulate the various relationships of ethnic minorities with the state (tribute, tax, service to state, legal system, elite co-optation, etc.). Such institutions have well-established traditions in both Russia and China, but in different ways and with different outcomes. They bore various names between the seventeenth and twentieth centuries, of which the better known include the early Soviet People’s Commissariat of Nationalities and the Qing Chinese Lifanyuan. Comparing their changing functions, tasks, and ideological bases over time represented one major challenge of the project; understanding these institutions within a theoretical framework of empire-building and continental colonialism was another.

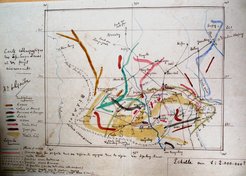

To launch this ambitious project, a workshop was organised in April 2011 on Administrative and Colonial Practices in Qing Ruled China that was attended by scholars from the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Mongolia, the People’s Republic of China, and the Republic of China (Taiwan). This conference, which emphasised the significance of structural configurations and central agencies of the ancien regime that had an impact in the republican period as well, was prepared by Sayana Namsaraeva, who carried out research in the First Historical Archive (Diyi lishi dang’an), the library of the National Committee for the Compilation of Qing History (Guojia qingshi bianzuan gongcheng), and the Institute of Qing History of the People’s University of China (Renming daxue qingshi yanjiusuo). Governmental documents connected with the Lifanyuan were one main focus; another was the management of ethnic diversity in Hulunbuir, a frontier zone bordering Russia’s Far East. The colonial strategies used by both empires to integrate peoples were of particular interest. These strategies are visible, for example, in negotiations over territorial assets and the disputed nomadic population. Attempts to control this particular frontier were concerned with the challenge of how to keep a mobile Mongolian and Tungusic-speaking population within colonial boundaries and how to co-opt their elites into imperial structures.

Furthermore, to arrive at a nuanced perspective on the emergence of the multi-national Qing Empire and continental colonialism, and given the lack of comparative approaches to the Lifanyuan and Libu (which were equally responsible for managing ethnic diversity in Ming-Qing China, albeit in different ways) and their subdivisions, two historians specialising in Inner Asian history were invited to collaborate on the project from autumn 2011 to spring 2014. These scholars, Dorothea Heuschert-Laage and Chia Ning, carried out four sub-projects which were based on unpublished archival material and the recently published Manchu-Mongol Lifanyuan Archives and Records (Qingchao qianqi lifanyuan man mengwen tiben, 24 vols., 2010) which offered a unique opportunity to work with new source material and, at the same time, to critically assess Qing Dynasty historiography on non-Chinese minorities.

Heuschert-Laage’s two projects focused on the role of Lifanyuan’s colonial administration for the Mongols. Combining institutional history and actors’ perspectives, her first investigation, entitled The Lifanyuan’s Scope of Responsibility over Mongolian Legal Matters in the Qing Dynasty, encompassed as many of the Mongol-related Lifanyuan competencies as possible: diplomacy and foreign relations, genealogy and marriage alliances, communication and tributary embassies, administration and law, ritual and religion, property and trade, and mobility and migration control. Developing the analysis around patronage-clientele networks and the incorporation of the Mongols into the Qing Chinese legal system, her final project, entitled Restricting Pastoral Mobility: The Territorial Integration of Mongols into the Qing Empire, focused particularly on questions of pastoral economy and landownership and examined Qing attempts to restrict and regulate pastoral mobility by creating internal boundaries and enclosing Mongol pastureland.

Although the Mongols had once been a powerful player in Eurasia, by the end of the Qing Dynasty (1912) their situation was reminiscent of that of colonised peoples in other parts of the world. To explain the changing modes of their integration into an administrative system with the emperor at the top, Heuschert-Laage examined the political techniques of patronage and the formalised language and expressions of courtesy that were part of this. She showed that the Qing, by re-interpreting the obligations of gift exchange, transformed the network of personal relationships with Mongolian leaders into a system with clearly defined rules to the effect that, during the late Qing, the façade of a patronage-clientele system was maintained in order to legitimise increasingly unequal power relations. Whereas techniques of patronage were developed long before the Qing came to power, the Lifanyuan now monitored and modified the practice of patronage: the emphasis shifted from recording what was ‘received’ to recording what was ‘given’, thus stressing the kindness and generosity of the emperor and relegating the Mongols to a subordinate role at the Inner Asian frontier.

Similar shifts towards unequal power relations and direct rule are documented in the changing concepts of territory, especially when land rights and the use of nomadic pastures were challenged by in-migrating Chinese farmers, and in legal controversies over jurisdictional competence that played an important role in re-defining Manchu-Mongolian relationships. What becomes evident from this analysis is, first, the change from a multi-jurisdictional legal order towards greater coherence and consistency. Like the changing forms of gift exchange and patronage, this shift towards incorporating the Mongols into the Qing Chinese legal system corresponds to the general trend towards formalisation and assimilation in other parts of Mongolian and Inner Asian cultures. Second, the Lifanyuan was contested along jurisdictional and administrative lines and its functions were continuously re-interpreted through the interplay between coloniser and colonised, centre and periphery – a feature attested for many colonial institutions. In mid-2014 Heuschert-Laage left the group and joined a research cluster initiated by Karenina Kollmar-Paulenz at the Institute for the Science of Religion and Central Asian Studies at the University of Bern.

Her research was complemented by two additional short-term projects brilliantly designed by Chia Ning, the leading expert in Lifanyuan studies. Her first research project, entitled Lifanyuan and Libu: institutional developments and agencies in Qing China, compared and contrasted the developments of these two distinct though cognate agencies. With the empire’s expansion, people came under the jurisdiction of various institutions so that different agencies were sometimes separately engaged with the administration of nationalities even within the same frontier region; this was the focus of her second project, entitled The Population in Nationality Categories and Their Institutional Affiliations in the Qing World.

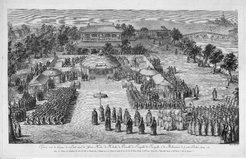

Chia Ning gives a precise description of the Lifanyuan’s differentiated procedures of indirect rule, employing various ‘social systems’ to govern different ‘social entities’, thus preserving ethnic identities, traditions, and local political orientations for a long time. Established in 1636, the Lifanyuan functioned as an institutional pillar in Qing empire-building even after indirect rule in the operative social systems was later converted into forms of direct governance and decision-making processes were increasingly centralised. Complementing the analysis of Lifanyuan’s involvement in Mongolian affairs, her research not only corroborates the thesis that colonial formats changed over time, but also enlarges our analytical framework by including the Libu (Board of Rites) in a comparison of the institutions in charge of Qing colonial affairs. Taking the ethnically and culturally diverse population of the Ming and Qing Empires as a starting point, she examines three different types of institution: 1) the Lifanyuan, introduced by the Qing, for Inner Asia; 2) the Libu in its Ming and Qing forms; and 3) the Six Boards for China proper. In some regions (Amdo, Qinghai), Lifanyuan and Libu responsibilities overlapped with regard to particular patronage-clientele activities (pilgrimage, court rituals, tribute), the processing of imperial examinations, and the supervision of Buddhist and Muslim affairs, leading to forms of close cooperation in colonial management. Both agencies, however, are but two of a series of institutions dealing with the ethnic diversity in imperial China. After it was relieved of its responsibilities in foreign affairs, the Lifanyuan continued to exist as Lifanbu (a revised name of the Lifanyuan starting in 1906) until 1912 and was soon re-established, first as the Board (1914) and later as the Commission (1928) of ‘Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs’, which until recently was still active in Taiwan and had a parallel ‘twin’ agency in the People’s Republic of China’s ‘State Nationality Affairs Commission’, founded in 1949. This continuity and the thick structure of China’s continental colonialism make it possible to bring trends of integration, from ‘difference’ to ‘sameness’ and from ‘indirect’ to ‘direct’, into a continental perspective.

My own investigations compared and contrasted the Chinese case with similar developments in the Russian Empire. Here the longue durée picture looks similar, though the specific evolution of political institutions is quite different. Imperial Russia’s foreign office included a ‘Department of Asian Affairs’ (established 1797) and an ‘Asian Department’ (1819, the de facto colonial office), which were supplemented by a number of indigenous self-governments and steppe dumas (indigenous self-administration). However, institutional centralisation took shape rather late in the form of the Stalin-era ‘People’s Commissariat of Nationalities’. The urge for ethnic-cultural integration surfaced in Russia especially during historical ruptures (1917, 1989-91), mirroring the oscillations in imperial cohesiveness often described as ‘dynastic’ or ‘administrative cycles’. Integration continues to be high on the agenda today, as shown by the establishment of the ‘Presidential Council for Intra-National Relationships’ in May 2012. Created by a presidential ukase (decree), the council has the aim of promoting a ‘single political nation’.

Results of this research have been continuously developed and published in various formats. In addition, all key studies found a prominent place in a volume edited by Chia Ning and myself and based on the conference mentioned above. In the book, entitled Managing Frontiers in Qing China, historians and anthropologists explore China’s imperial expansion in Inner Asia, focusing on early Qing empire-building in Mongolia, Xinjiang, Tibet, and beyond; also included are Central Asian perspectives and comparisons to Russia’s Asian empire. Using institutional-history and historical-anthropology approaches, the book engages with two Qing agencies (the Lifanyuan and Libu), that were involved in the governance of non-Han groups. It offers a broad overview of these agencies and revises and assesses the state of affairs in this under-researched field. This “first comprehensive study of a key institution of the Qing dynasty: the Lifanyuan”, Nicola Di Cosmo writes in his preface, “destabilizes the centrality of Western imperial narratives more radically than approaches that simply assert differences between Asian and European empires”, making it a study that “forces theorists to grapple with a practice of empire-building that cannot be confined to the Chinese political tradition”. Using a contrastive approach that compares the Lifanyuan with the Libu, the northern frontiers with the southern ones, and the early stages with later developments, the book also benefits from the interdisciplinary cross-fertilisation of various historical, anthropological, and philological methods.

The Lifanyuan was remarkable among Qing governmental institutions. Its main function was to deal with the affairs of incorporated nations and to communicate imperial policies and decisions to the imperial peripheries of Inner Asia. This included legislation, taxation, trade, diplomacy, and social welfare, and encompassed civil, military, and cultural matters. By maintaining forms of indirect rule and separate administration in Inner Asia, the Lifanyuan offered a model of integration by difference that existed as an alternative to the Qing’s assimilatory policy (integration by sameness, or gaitu guiliu, ‘replacing the locals with residents’) pursued in the colonisation process in many parts of China’s southern frontier.

Lifanyuan and Libu responsibilities significantly overlapped; both had important duties in non-Chinese affairs on which other ministries did not concentrate since Ming times. Internal relations with indigenous peoples were generally managed through the Chinese prefectural structures according to the traditional ‘Tusi’ (native chieftain) system, and external relations with tribute-paying countries were managed through the Libu. The Libu was also in charge of imperial examinations and of implementing measures that supported the Chinese political tradition and Confucian moral order. As institutions that fall at the junction of the Ming and Qing periods and their world views and integration strategies, the Libu and Lifanyuan have always been of considerable interest not only for Chinese historians studying socio-cultural processes and the institutional expression of Qing policies but also for historical anthropologists studying the changing practices and habitus of imperial governance. Against this background the book explores the imperial policies towards minority groups and the changing ways these groups were classified.

While integration strategies in multi-national empires may vary across time and space, they are all attempts to address essentially the same challenge: to maintain cross-epochal cohesiveness and to guarantee certain rights of national self-determination. In the case of Russia, eighteenth-century Enlightenment scholars from Western Europe responded to the call to take stock of the empire’s riches, peoples, and languages; their assiduous recording of statistics and classification paved the way for a mission civilisatrice and the modern approach to nationalities. In Ming and Qing China, on the other hand, there was remarkably less interest in creating a detailed ethnic typology of the empire’s peoples. Instead a tradition prevailed of subsuming non-Han Chinese under collective names formed into ethnocentric stereotypes (Fan, Meng, Hui, etc.) using a dichotomous distinction between ‘inner’ (nei) and ‘outer’ (wai) domains. This distinction was accompanied by a messianic belief in the importance of Confucianism for promoting the ‘barbarians’ from a lower ‘raw’ (sheng) to a higher ‘cooked’ (shu) status. Western concepts of ‘ethnicity’ and ‘race’ did not reach China until the late nineteenth century. However, independently of each other, though with some degree of mutual influence that continued into socialist times, both empires – China and Russia – invented and developed central institutions, needed even today, to control and influence ethnic-cultural diversity, to govern the civilisational frontier, to design appropriate keystones for their nationalities policies, and to implement strategies of integration for the sake of imperial cohesion.

All these studies benefitted greatly from the stimulating discussions and empirical findings of Simon Schlegel, Fan Zhang, Elisa Kohl-Garrity, and Elzyata Kuberlinova, who in in their doctoral projects investigated various aspects of the historical situation of ethnic minorities in multi-national states and provided fresh insight from their field sites in Tibet, Mongolia, Kalmykia, and the Ukraine.

With a focus on ethnicity concepts as part of a timeless ‘boundary maintaining mechanism’ (Fredrik Barth), Simon Schlegel’s research illuminates integration processes and minority-state relations along the northern shore of the Black Sea. In his doctoral thesis, entitled The Making of Ethnicity in Southern Bessarabia: tracing the histories of an ambiguous concept in a contested land (defended in spring 2016), Schlegel corroborates the idea that the social construction of ethnic boundaries in the Russian Empire underwent historical changes: whereas ‘religion’ had been the main identity marker in the early nineteenth century, it has been replaced by ‘ethnicity’ as the modern category of classification. The research on the mechanisms of ethnic distinction in Bessarabia investigated questions of ethnic boundary-making in this south-westernmost part of the Ukraine – an area that long served as a buffer area between the Ottoman, Russian, and Habsburg empires. The territory became part of Russia in 1812, and within a few decades the empire had implemented its institutions, practices, and orientations in its new marginal province. This process included the increasing importance of classifying people according to categories that were connected with specific rights and duties. Consequently, ethnic groups were more and more perceived as distinct entities in an ethnically heterogeneous frontier region. In the late medieval period, this area was still part of a cultural contact zone par excellence, as I’ve demonstrated in my research on the Slavia Asiatica.

With her doctoral project on the Qing imperial order in Tibet, Fan Zhang contributed to our discussion of Sino-Tibetan relationships and political strategies in the formation of multi-ethnic states within the Lifanyuan research framework. Her studies focused on the techniques, procedures and institutions developed or invented by the Qing when annexing and incorporating Tibet; as a counterweight to these state-centred perspectives she also considered subaltern voices of the local elite. This research on Inner Asia is complemented by the doctoral project of Elisa Kohl-Garrity, which tackles Mongolian notions of respect that are important for an understanding of history as moral authority. The study analyses the changing formats and framing of respect in various historiographical projects and their specific socio-economic contexts. Combining interviews with in-depth study of representative chronicles from the thirteenth to the eighteenth centuries, she explores how respect as a resource of social cohesion is connected with kinship, customs, laws, traditions, religion (Buddhism), and history. Finally, Elzyata Kuberlinova also addresses the connection between religion and social cohesion using the case of the Kalmyks, a western Mongol people who migrated from Inner Asia into southern Russia in the early seventeenth century. She shows how the imperial administration governed minorities through religious institutions and how the Kalmyk clergy responded to these governmental schemes, demonstrating a variety of forms of resistance to central rule.

To sum up, this larger project on Ethnic Minorities and the State in Eurasia (2009-2016) has brought many results and a good yield of fine publications. Furthermore, it created the venue for a follow-up research project on global, regional, and local perspectives to be developed in the years to come. Continental colonialism and its derivatives, such as internal colonialism, is a worldwide phenomenon. Europe and Asia are particularly fruitful for studying the manifestations of this, although there are also well-known cases from the Americas and Africa. As a central theme of our previous research, this notion became a key concept that was presented and developed during an international conference in July 2016. Bringing together anthropologists, sociologists and historians, the conference aimed to expand the range of places and topics addressed in the anthropology of colonialism, including cases of internal colonialism that grew out of overseas and settler colonialism in North America and Canada, Hispanic America, India, and South Africa.

On a regional level, Buddhist statecraft is an intriguing concept applicable not only to Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia, as Patrice Ladwig has shown, but to Tibetan Mahayana Buddhism in Inner Asia as well. This idea was discussed and developed into a research topic (‘Buddhist reform thinking under early Soviet rule’) during a workshop on ‘Sino-Tibetan Relations and Tibetan Self-Perception in Historical Perspective’ organised together with Leonard van der Kuijp (Harvard University) and a round table on ‘Buddhist Temple Economies in Urban Asia’ organised jointly with Christoph Brumann from our institute and Karenina Kollmar-Paulenz (University of Bern). Last but not least, the local view is of lasting importance, since anthropology and history deal with places, events, and peoples on the ground. Here, a soon-to-be-completed book project entitled “(…) Because nobody will save the allogeneous people unless they save themselves (…)” will contribute to the historical anthropology of the Buryats and Kalmyks, who have lived in Russian territory since the early seventeenth century and are the only Mongol-speaking Buddhist peoples in this multi-ethnic state. The changing relations between ethnic minorities and multi-national states is a topic that has remained relevant across the centuries, and historical research will continue to be an invaluable analytical tool for social and cultural anthropologists to enhance our understanding of recurrent dynamics, ethno-political fragmentations, and cultural identities.

Publications

Heuschert-Laage, Dorothea. 2011. “Defining a Hierarchy: Formal Requirements for Manchu-Mongolian Correspondence Issued in 1636.” Quaestiones Mongolorum Disputatae 7: 48-58.

Heuschert-Laage, Dorothea. 2012a. “Modes of Legal Proof in Traditional Mongolian Law (16th-19th Centuries).” In Proceedings of the 10th International Congress of Mongolists. Volume I: Prehistoric and Historical Periods of Mongolia’s Relations with Various Civilizations, edited by D. Tumurtogoo, 286-88. Ulaanbaatar: International Association for Mongol Studies.

Heuschert-Laage, Dorothea. 2012b. State Authority Contested along Jurisdictional Boundaries. Qing legal policy towards the Mongols in the 17th and 18th centuries. Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology Working Paper 138.

Heuschert-Laage, Dorothea. 2013. “Guojia quanli zai sifa lingyu de juezhu – 17, 18 shiji Qingchao dui Menggu de falü zhengce” [Struggling for authority in the field of justice: Qing legal policies towards Mongols in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.] In Zhongguo bianjiang minzu yanjiu - Studies of China’s Frontier Regions and Nationalities 7, edited by Dalizhabu (Darijab), 351-68. Beijing: Zhongyang minzudaxue chubanshe.

Heuschert-Laage, Dorothea. 2014a. “From Personal Network to Institution Building: The Lifanyuan, Gift Exchange and the Formalization of Manchu–Mongol Relations.” History and Anthropology 25,5: 648-69.

Heuschert-Laage, Dorothea. 2014b. “The Lifanyuan and the Six Boards in the First Years of the Qing Dynasty: Clarifying Roles and Responsibilities.” In Manmeng dang’an yu Menggu shi yanjiu [Manchu-Mongolian archives and the study of Mongolian history], edited by Wuyunbilige (Oyunbilig), 5-18. Shanghai: Guji chubanshe.

Heuschert-Laage, Dorothea. 2017. “Manchu-Mongolian Controversies over Judicial Competence and the Formation of the Lifanyuan.” In Managing Frontiers in Qing China: The Lifanyuan and Libu Revisited (Brill’s Inner Asian Library 35), edited by Dittmar Schorkowitz and Chia Ning, 224-53. Leiden, Boston: Brill.

Kohl-Garrity, Elisa. 2015. “Kinship as ‘Culture’? Approach Towards the Meaning of Soyol (‘Culture’) as a Relationship of Seniority in Mongolia.” In Perspektiven auf Verwandtschaft: Soziale Beziehungen in Europa und Asien (Berliner Beiträge zur Ethnologie 38), edited by Miriam Benteler, 43–68. Berlin: Weißensee Verlag.

Kohl-Garrity, Elisa. 2017. “Contextualising Global Processes in Negotiating the ‘Custom of Respect’ in Ulaanbaatar.” In Mongolian Responses to Globalisation Processes (Bonner Asienstudien 13), edited by Ines Stolpe, Judith Nordby, and Ulrike Gonzales, 105-28. Berlin: EB-Verlag.

Ladwig, Patrice. 2009a. “Narrative Ethics: The Excess of Giving and Moral Ambiguity in the Lao Vessantara-Jataka.” In The Anthropology of Moralities, edited by Monica Heintz, 136-60. New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Ladwig, Patrice. 2009b. „Prediger der Revolution: Der buddhistische Mönchsorden in Laos und seine Verbindungen zur Kommunistischen Bewegung (1957-1975).“ Jahrbuch für Historische Kommunismusforschung XV: 181-97.

Ladwig, Patrice. 2011. “The Genesis and Demarcation of the Religious Field: Monasteries, State Schools, and the Secular Sphere in Lao Buddhism (1893-1975).” Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 26,2: 196-223.

Ladwig, Patrice. 2012a. “Ontology, Materiality and Spectral Traces: Methodological Thoughts on Studying Lao Buddhist Festivals for Ghosts and Ancestral Spirits.” Anthropological Theory 12,4: 427-47.

Ladwig, Patrice. 2012b. “Visitors from Hell: Transformative Hospitality to Ghosts in a Lao Buddhist Festival.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 18 (Supplement S1): S90-S102.

Ladwig, Patrice. 2012c. “Feeding the Dead: Ghosts, Materiality and Merit in a Lao Buddhist Festival for the Deceased.” In Buddhist Funeral Cultures of Southeast Asia and China, edited by Paul Williams and Patrice Ladwig, 119-41. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ladwig, Patrice. 2013a. “Haunting the State: Rumours, Spectral Apparitions and the Longing for Buddhist Charisma in Laos.” Asian Studies Review 37,4: 509-26.

Ladwig, Patrice. 2013b. “Schools, Ritual Economies, and the Expanding State: the Changing Roles of Lao Buddhist Monks as ‘traditional intellectuals’.” In Buddhism, Modernity, and the State in Asia: Forms of Engagement, edited by John Whalen-Bridge and Pattana Kitiarsa, 63-91. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ladwig, Patrice. 2014a. “Mobile phone monk.” In Figures of Southeast Asian Modernity, edited by Erik Harms, Johan Lindquist and Joshua Barker, 97-99. Honolulu: Hawai’i University Press.

Ladwig, Patrice. 2014b. “Millennialism, Charisma and Utopia: Revolutionary Potentialities in Pre-modern Lao and Thai Theravāda Buddhism.” Politics, Religion & Ideology 15,2: 308-29.

Ladwig, Patrice. 2015. “Worshipping Relics and Animating Statues: Transformations of Buddhist Statecraft in Contemporary Laos.” Modern Asian Studies 49,6: 1875-1902.

Ladwig, Patrice. 2016. “Religious Place Making. Civilized Modernity and the Spread of Buddhism Among the Cheng, a Mon-Khmer Minority in Southern Laos.” In Religion, Place and Modernity, edited by Michael Dickhardt and Andrea Lauser, 95-125. Leiden: Brill.

Ladwig, Patrice. 2018a. “The Indianization and Localization of Textual Imaginaries: Theravada Buddhist Statecraft in Mainland Southeast Asia and Laos in the Context of Civilizational Analysis. In: Anthropology and Civilizational Analysis: Eurasian Explorations, edited by Johann P. Arnason and Chris Hann, 155-91. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Ladwig, Patrice. 2018b. “Imitations of Buddhist Statecraft. The Patronage of Lao Buddhism and the Reconstruction of Relic Shrines and Temples in Colonial French Indochina.” Social Analysis 62,2.

Patrice Ladwig, Ricardo Roque, Oliver Tappe, Christoph Kohl, and Cristiana Bastos. 2012. Fieldwork Between Folders: Fragments, Traces, and the Ruins of Colonial Archives. Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology Working Paper 141.

Ladwig, Patrice, and James Mark Shields. 2014a. “Introduction.” Politics, Religion & Ideology 15,2: 187-204.

Ladwig, Patrice, and James Mark Shields (eds.). 2014b. Against Harmony? Radical and Revolutionary Buddhism(s) in Thought and Practice. Politics, Religion & Ideology 15,2.

Ladwig, Patrice, and Paul Williams. 2012a. “Introduction: Buddhist funeral cultures.” In Buddhist Funeral Cultures of Southeast Asia and China, edited by Paul Williams and Patrice Ladwig, 1-20. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ladwig, Patrice, and Paul Williams (eds.). 2012b. Buddhist Funeral Cultures of Southeast Asia and China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ladwig, Patrice, and Ricardo Roque. 2018. “Introduction. Mimetic Governmentality, Colonialism, and the State.” Social Analysis 62,2: 1-27.

Namsaraeva, Sayana. 2010. “The Metaphorical Use of Avuncular Terminology in Buriad Diaspora Relationships with Homeland and Host Society.” Inner Asia: Occasional Papers 12: 201-230.

Namsaraeva, Sayana. 2012a. “Ritual, Memory and the Buriad Diaspora Notion of Home.” In Frontier Encounters: Knowledge and Practice at the Russian, Chinese and Mongolian Border, edited by Frank Billé, Grégory Delaplace, and Caroline Humphrey, 137-63. Cambridge : Open Book Publisher.

Namsaraeva, Sayana. 2012b. “Saddling up the Border: A Buriad Community within the Russian-Chinese Frontier Space.” In Frontiers and Boundaries: Encounters on China’s Margins, edited by Zsombor Rajkai and Ildikó Bellér-Hann, 223-45. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Namsaraeva, Sayana. 2012c. „Die Rolle der mongolischen Sprache in interkulturellen Kontakten zwischen Rußland und China (im Verlauf des 18. Jahrhunderts).“ In Die Erforschung Sibiriens im 18. Jahrhundert: Beiträge der Deutsch-Russischen Begegnungen in den Franckeschen Stiftungen, edited by Wieland Hintzsche and Joachim Otto Habeck, 147-58. Halle/Saale: Verlag der Franckeschen Stiftungen zu Halle.

Namsaraeva, Sayana. 2014. China - Russia North Asian Border History. Cambridge: White Horse Press.

Ning, Chia. 2012. Lifanyuan and the Management of Population Diversity in Early Qing (1636-1795). Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology Working Paper 139.

Ning, Chia. 2013. “Qingchai qianqi lifanyuan manmengwen tiben zhong menggu chojintanjiu” 《清朝前期理藩院满蒙文题本》中蒙古朝觐探究 [Study on the Mongol Pilgrimage to the Manchu Emperor Based on two Manchu tiben.] In A Collection of Qing Studies in honor of Professor Wang Zhonghan, edited by Chen Li, 497-513. Beijing: National University for Nationalities Press.

Ning, Chia. 2015. “The Qing Lifanyuan and the Solon People of the 17th-18th Centuries.” Athens Journal of History 1,4: 253-66.

Ning, Chia. 2017a. “Lifanyuan and Libu in Early Qing Empire Building.” In Managing Frontiers in Qing China: The Lifanyuan and Libu Revisited (Brill’s Inner Asian Library 35), edited by Dittmar Schorkowitz and Chia Ning, 43-69. Leiden, Boston: Brill.

Ning, Chia. 2017b. “Lifanyuan and Libu in the Qing Tribute System.” In Managing Frontiers in Qing China: The Lifanyuan and Libu Revisited (Brill’s Inner Asian Library 35), edited by Dittmar Schorkowitz and Chia Ning, 144-83. Leiden, Boston: Brill.

Ning, Chia, and Dittmar Schorkowitz. 2017a. “Introduction.” In Managing Frontiers in Qing China: The Lifanyuan and Libu Revisited (Brill’s Inner Asian Library 35), edited by Dittmar Schorkowitz and Chia Ning, 1-42. Leiden, Boston: Brill.

Ning, Chia, and Dittmar Schorkowitz (eds.). 2017b. Managing Frontiers in Qing China: The Lifanyuan and Libu Revisited (Brill’s Inner Asian Library 35). Leiden, Boston: Brill.

Schlegel, Simon. 2013. “Funkcii i značenie ėtničnosti v Južnoj Bessarabii: nekotorye issledovatel’skie perspektivy.” Lukomor‘ja: Археология, этнология, история северо-западного Причерноморья 5: 69-80.

Schlegel, Simon. 2016a. The Making of Ethnicity in Southern Bessarabia: Tracing the Histories of an Ambiguous Concept in a Contested Land. PhD diss., Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg.

Schlegel, Simon. 2016b. “Who is Going to Fix the Road to Europe?” Anthropology News 57,3-4: 20.

Schlegel, Simon. 2017a. „Ethnische Minderheiten an der ukrainischen Peripherie: Diversität ohne kulturelle Unterschiede?“ In Neuer Nationalismus im östlichen Europa: Kulturwissenschaftliche Perspektiven, edited by Irene Götz, Klaus Roth, and Marketa Spiritova, 151-68. Bielefeld: transcript.

Schlegel, Simon. 2017b. “Ukrainian Nation Building and Ethnic Minority Associations: the Case of Southern Bessarabia.” In Transnational Ukraine?: Networks and Ties that Influence(d) Contemporary Ukraine, edited by Timm Beichelt and Susann Worschech, 203-23. Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

Schlegel, Simon. 2017c. “The Resilience of Soviet Ethnicity Concepts in a Post-Soviet Society: Studying the Narratives and Techniques that Maintain Ethnic Boundaries.” Anthropology of East Europe Review 35,1: 1-18.

Schlegel, Simon. 2018. “How Could the Gagauz Achieve Autonomy and What has it Achieved for Them? A Comparison Among Neighbours on the Moldova-Ukrainian Border.” Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe 17,1: 1-23.

Schlegel, Simon. (Forthcoming). The Making of Ethnicity in Southern Bessarabia: Tracing the History of an Ambiguous Concept in a Contested Land (Eurasian Studies Library, ed. by Dittmar Schorkowitz and David Schimmelpenninck van der Oye.) Leiden: Brill.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2009. Erinnerungskultur, Konfliktdynamik und Nationsbildung im nördlichen Schwarzmeergebiet. Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology Working Paper 118.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2010a. „Geschichte, Identität und Gewalt im Kontext postsozialistischer Nationsbildung.“ Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 135,1: 99-160.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2010b. „Karabach, mon amour.“ In Lösungsansätze für Berg-Karabach/Arzach: Selbstbestimmung und der Weg zur Anerkennung, edited by Vahram Soghomonyan, 177-92. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2010c. „Armenier in der Sowjetunion und ihren Nachfolgestaaten (1937-1994).“ In Lexikon der Vertreibungen. Deportation, Zwangsaussiedlung und ethnische Säuberung im Europa des 20. Jahrhunderts, edited by Detlef Brandes, Holm Sundhaussen, and Stefan Troebst, 49-52. Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau Verlag.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2010d. „Azeri (1988-1994).“ In Lexikon der Vertreibungen. Deportation, Zwangsaussiedlung und ethnische Säuberung im Europa des 20. Jahrhunderts, edited by Detlef Brandes, Holm Sundhaussen, and Stefan Troebst, 58-60. Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau Verlag.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2010e. „Balkaren (1944-1945).“ In Lexikon der Vertreibungen. Deportation, Zwangsaussiedlung und ethnische Säuberung im Europa des 20. Jahrhunderts, edited by Detlef Brandes, Holm Sundhaussen, and Stefan Troebst, 63-64. Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau Verlag.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2010f. „Georgier (1991-1993, 1998).“ In Lexikon der Vertreibungen. Deportation, Zwangsaussiedlung und ethnische Säuberung im Europa des 20. Jahrhunderts, edited by Detlef Brandes, Holm Sundhaussen, and Stefan Troebst, 265-67. Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau Verlag.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2010g. „Kabardiner (1944).“ In Lexikon der Vertreibungen. Deportation, Zwangsaussiedlung und ethnische Säuberung im Europa des 20. Jahrhunderts, edited by Detlef Brandes, Holm Sundhaussen, and Stefan Troebst, 324-26. Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau Verlag.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2010h. „Kalmücken (1943-1945).“ In Lexikon der Vertreibungen. Deportation, Zwangsaussiedlung und ethnische Säuberung im Europa des 20. Jahrhunderts, edited by Detlef Brandes, Holm Sundhaussen, and Stefan Troebst, 326-29. Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau Verlag.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2010i. „Karapapaken-Terekeme (1944, 1989).“ In Lexikon der Vertreibungen. Deportation, Zwangsaussiedlung und ethnische Säuberung im Europa des 20. Jahrhunderts, edited by Detlef Brandes, Holm Sundhaussen, and Stefan Troebst, 330-31. Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau Verlag.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2010j. „Karatschaier (1943-1945).“ In Lexikon der Vertreibungen. Deportation, Zwangsaussiedlung und ethnische Säuberung im Europa des 20. Jahrhunderts, edited by Detlef Brandes, Holm Sundhaussen, and Stefan Troebst, 331-34. Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau Verlag.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2010k. „Kurden (1937, 1944/45, 1948, 1988-1993).“ In Lexikon der Vertreibungen. Deportation, Zwangsaussiedlung und ethnische Säuberung im Europa des 20. Jahrhunderts, edited by Detlef Brandes, Holm Sundhaussen, and Stefan Troebst, 370-73. Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau Verlag.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2010l. „Mes’cheten-Türken (1937, 1944/45, 1949-1951, 1989-2005).“ In Lexikon der Vertreibungen. Deportation, Zwangsaussiedlung und ethnische Säuberung im Europa des 20. Jahrhunderts, edited by Detlef Brandes, Holm Sundhaussen, and Stefan Troebst, 419-22. Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau Verlag.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2010m. „Osseten (1989-1993).“ In Lexikon der Vertreibungen. Deportation, Zwangsaussiedlung und ethnische Säuberung im Europa des 20. Jahrhunderts, edited by Detlef Brandes, Holm Sundhaussen, and Stefan Troebst, 490-92. Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau Verlag.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2010n. „Tschetschenen und Inguschen (1943-1945, 1992-2006).“ In Lexikon der Vertreibungen. Deportation, Zwangsaussiedlung und ethnische Säuberung im Europa des 20. Jahrhunderts, edited by Detlef Brandes, Holm Sundhaussen, and Stefan Troebst, 654-60. Wien, Köln, Weimar: Böhlau Verlag.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2012a. “Historical Anthropology in Eurasia ‘… and the Way Thither’.” History and Anthropology 23,1: 37-62.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2012b. “Cultural Contact and Cultural Transfer in Medieval Western Eurasia.” Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia 40,3: 84–94.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2012c. “Культурные контакты и культурная трансмиссия в западной Евразии в эпоху средневековья.” Археология, этнография и антропология Евразии 51,3: 84-94.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2012d. „Проблема происхождения восточных славян и образование Киевской Руси: Опыт пере-оценки в постсоветской историографии.“ Lukomor‘ja: Археология, этнология, история северо-западного Причерноморья 4 [2010]: 110-145.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2013a. „Азербайджанцы (1988-1994).“ In Энциклопедия изгнаний: депортация, принудительное выселение и этническая чистка в Европе в XX веке, edited by Д. Брандес, Х. Зундхауссен, Ш. Трëбст, 20-21. Москва: РОССПЭН.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2013b. „Армяне в СССР и на постсоветском пространстве (1937-1994).“ In Энциклопедия изгнаний: депортация, принудительное выселение и этническая чистка в Европе в XX веке, edited by Д. Брандес, Х. Зундхауссен, Ш. Трëбст, 35-38. Москва: РОССПЭН.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2013c. „Балкарцы (1944-1945).“ In Энциклопедия изгнаний: депортация, принудительное выселение и этническая чистка в Европе в XX веке, edited by Д. Брандес, Х. Зундхауссен, Ш. Трëбст, 44-46. Москва: РОССПЭН.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2013d. „Грузины (1991-1993, 1998).“ In Энциклопедия изгнаний: депортация, принудительное вы-селение и этническая чистка в Европе в XX веке, edited by Д. Брандес, Х. Зундхауссен, Ш. Трëбст, 142-44. Москва: РОССПЭН.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2013e. „Кабардинцы (1944).“ In Энциклопедия изгнаний: депортация, принудительное выселение и этническая чистка в Европе в XX веке, edited by Д. Брандес, Х. Зундхауссен, Ш. Трëбст, 207-8. Москва: РОССПЭН.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2013f. „Калмыки (1943-1945).“ In Энциклопедия изгнаний: депортация, принудительное выселение и этническая чистка в Европе в XX веке, edited by Д. Брандес, Х. Зундхауссен, Ш. Трëбст, 212-15. Москва: РОССПЭН.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2013g. „Карапапахи-терекеменцы (1944, 1989).“ In Энциклопедия изгнаний: депортация, принудительное выселение и этническая чистка в Европе в XX веке, edited by Д. Брандес, Х. Зундхауссен, Ш. Трëбст, 216-17. Москва: РОССПЭН.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2013h. „Карачаевцы (1943-1945).“ In Энциклопедия изгнаний: депортация, принудительное высе-ление и этническая чистка в Европе в XX веке, edited by Д. Брандес, Х. Зундхауссен, Ш. Трëбст, 217-20. Москва: РОССПЭН.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2013i. „Курды (1937, 1944-1945, 1948, 1988-1993).“ In Энциклопедия изгнаний: депортация, принудительное выселение и этническая чистка в Европе в XX веке, edited by Д. Брандес, Х. Зундхауссен, Ш. Трëбст, 240-42. Москва: РОССПЭН.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2013j. „Осетинцы (1989-1993).“ In Энциклопедия изгнаний: депортация, принудительное выселение и этническая чистка в Европе в XX веке, edited by Д. Брандес, Х. Зундхауссен, Ш. Трëбст, 402-4. Москва: РОССПЭН.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2013k. „Турки-месхетинцы (1937, 1944-1945, 1949-1951, 1989-2005).“ In Энциклопедия изгнаний: депортация, принудительное выселение и этническая чистка в Европе в XX веке, edited by Д. Брандес, Х. Зундхауссен, Ш. Трëбст, 568-71. Москва: РОССПЭН.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2013l. „Чеченцы и ингуши (1943-1945, 1992-2006).“ In Энциклопедия изгнаний: депортация, принудительное выселение и этническая чистка в Европе в XX веке, edited by Д. Брандес, Х. Зундхауссен, Ш. Трëбст, 627-32. Москва: РОССПЭН.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2013m. „Integration der Kulturen – Kultur der Integration.“ In Integrationskulturen in Europa, edited by Rüdiger Fikentscher, 62-71. Halle/Saale: Mitteldeutscher Verlag.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2014a. „Akkulturation und Kulturtransfer in der Slavia Asiatica.“ In Akkulturation im Mittelalter (Vorträge und Forschungen 78), edited by Reinhard Härtel, 137-63. Sigmaringen: Jan Thorbecke Verlag.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2014b. “1994-2014: Minden Nyugodt a Karabahi Fronton?“ [1994-2014: All Quiet on the Karabakh Front?]. In Politikai krízisek Európa peremén: a Kaukázustól a Brit-Szigetekig [Political Crises on the Outskirts of Europe: From the Caucasus to the British Isles], edited by Bálint Kovács, and Hakob Matevosyan, 159-75. Budapest: Magyar Napló.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2015. Imperial Formations and Ethnic Diversity: Institutions, Practices, and Longue Durée Illustrated by the Example of Russia. Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology Working Paper 165.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar. 2017. “Dealing with Nationalities in Imperial Formations: How Russian and Chinese Agencies Managed Ethnic Diversity in the 17th to 20th Centuries.” In Managing Frontiers in Qing China: The Lifanyuan and Libu Revisited (Brill’s Inner Asian Library 35), edited by Dittmar Schorkowitz and Chia Ning, 389-434. Leiden, Boston: Brill.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar, Stamatios Gerogiorgakis and Roland Scheel. 2011. „Kulturtransfer vergleichend betrachtet.“ In ),Integration und Desintegration der Kulturen im europäischen Mittelalter (Europa im Mittelalter. Abhandlungen und Beiträge zur historischen Komparatistik 18) edited by Michael Borgolte, Julia Dücker, Marcel Müllerburg and Bernd Schneidmüller, 385-466. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar, and Chia Ning. 2017a. “Introduction.” In Managing Frontiers in Qing China: The Lifanyuan and Libu Revisited (Brill’s Inner Asian Library 35), edited by Dittmar Schorkowitz and Chia Ning, 1-42. Leiden, Boston: Brill.

Schorkowitz, Dittmar, and Chia Ning (eds.). 2017b. Managing Frontiers in Qing China: The Lifanyuan and Libu Revisited (Brill’s Inner Asian Library 35). Leiden, Boston: Brill.

Tappe, Oliver. 2009. „Nachbarschaftsstreit am Mekong: König Anuvong und die Geschichte der prekären Lao-Thai-Beziehung.“ Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies 2,1: 6-29.

Tappe, Oliver. 2010. “The Escape from Phonkheng Prison: Revolutionary Historiography in the Lao PDR.” In Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Lao Studies, edited by Karen L. Adams and Thomas J. Hudak, 237-54. Tempe: Southeast Asia Council, Center for Asian Research, Arizona State University.

Tappe, Oliver. 2011a. “From Revolutionary Heroism to Cultural Heritage: Museum, Memory and Representation in Laos.” Nations and Nationalism 17,3: 604-626.

Tappe, Oliver. 2011b. “Memory, Tourism, and Development: Changing Sociocultural Configurations and Upland-lowland Relations in Houaphan Province, Lao PDR.” Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 26,2: 174–95.

Tappe, Oliver. 2012a. “Révolution, héritage culturel et stratégies de légitimation: exemples à partir de l‘historiographie et de l‘iconographie officielles.” In Laos: sociétés et pouvoirs, edited by Vanina Bouté and Vatthana Pholsena, 69-92. Paris: Les Indes Savantes.

Tappe, Oliver. 2012b. „Kollateralschäden: Landreform und Landverknappung in Laos.“ Südostasien 1: 25-27.

Tappe, Oliver. 2012c. „Religion in Laos.“ In Handbuch der Religionen der Welt. Afrika und Asien 2, edited by Markus Porsche-Ludwig and Jürgen Bellers, 1165-70. Nordhausen: Bautz.

Tappe, Oliver. 2013a. “National Lieu de Mémoire vs. Multivocal Memories: The Case of Viengxay, Lao PDR.” In Interactions with a Violent Past: Reading Post-conflict Landscapes in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, edited by Vatthana Pholsena and Oliver Tappe, 46-77. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press.

Tappe, Oliver. 2013b. “Faces and Facets of the Kantosou Kou Xat – the Lao ‘National Liberation Struggle’ in State Commemoration and Historiography.” Asian Studies Review 37,4: 433-50.

Tappe, Oliver. 2013c. „Thailand und Laos – Eine historische Hassliebe.“ In Thailand: Facetten einer südostasiatischen Kultur, edited by Orapim Bernart and Holger Warnk, 35-68. München: Edition Global.

Tappe, Oliver. 2013d. “Phak-lat kap pasason lao banda phao: Narrative, Iconic and Performative Aspects of Political Authority in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic.” In Proceedings of the Workshop ‘Authoritarian State, Weak State, Environmental State? Contradictions of Power and Authority in Laos’, edited by Keith Barney and Simon Creak, 25–46. Kyoto: Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University.

Tappe, Oliver. 2015a. “Introduction: Frictions and Fictions - Intercultural Encounters and Frontier Imaginaries in Upland Southeast Asia.” The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 16,4: 317-22.

Tappe, Oliver. 2015b. “A Frontier in the Frontier: Socio-political Dynamics and Colonial Administration in the Lao-Vietnamese Borderlands.” The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 16,4: 368-87.

Tappe, Oliver. 2017. “Shaping the National Topography: The Party-State, National Imageries, and Questions of Political Authority.“ In: Changing Lives in Laos: Society, Politics, and Culture in a Post-Socialist State, edited by Vanina Bouté and Vatthana Pholsena, 56-80. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press.

Tappe, Oliver. 2018a. “Frontier as Civilization? Sociocultural dynamics in the Uplands of Southeast Asia.” In: Anthropology and Civilizational Analysis: Eurasian Explorations, edited by Johann P. Arnason and Chris Hann, 193-218. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Tappe, Oliver. 2018b. “Variants of Frontier Mimesis: Colonial Encounter and Intercultural Interaction in the Lao-Vietnamese Uplands.“ Social Analysis 62,2.

Tappe, Oliver, and Volker Grabowsky. 2011. “Important Kings of Laos: Translation and Analysis of a Lao Cartoon Pamphlet.” Journal of Lao Studies 1,2: 1-44.

Tappe, Oliver, Patrice Ladwig, Ricardo Roque, Christoph Kohl, and Cristiana Bastos. 2012. Fieldwork Between Folders: Fragments, Traces, and the Ruins of Colonial Archives. Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology Working Paper 141, http://www.eth.mpg.de/cms/de/publications/working_papers/ wp0141.

Tappe, Oliver, and Vatthana Pholsena. 2013a. “The ‘American War’, Post-conflict Landscapes, and Violent Memories.” In Interactions with a Violent Past: Reading Post-conflict Landscapes in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, edited by Vatthana Pholsena and Oliver Tappe, 1-18. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press.

Tappe, Oliver, and Vatthana Pholsena (eds.). 2013b. Interactions with a Violent Past: Reading Post-conflict Landscapes in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press.

Zhang, Fan. 2014a. “Grass-root Official in the Ideological Battlefield: Re-evaluation of the Study of the Amban in Tibet.” In Political Strategies of Identity Building in Non-Han Empires in China (Asiatische Forschungen 157), edited by Francesca Fiaschetti and Julia Schneider, 225-54. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Zhang, Fan. 2014b. “从喜德林废墟重构“热振事件”并重估摄政拉章之功能“ [On the Ruin of bzhi deb gling: Reconstructing the Function of Regent labrang]. Xizang Dang’an [Tibetan Archive] 18,1: 32-40.