Is there a globalization - migration nexus?

Author: Attila Melegh

Eastern Europe and Eastern Asia Compared

During the last 30 years migration levels have risen sharply. This change is associated with the opening up of national markets by global capital. The affinity between the mobility of capital and the movement of people can be explained through recourse to the Polanyian notion of disembeddedness. The increasing role of foreign investment in the 1990s and the 2000s was associated with privatization, the closing down of local industries, neoliberal (pro-market) shifts in economic policy and the appearance of transnational companies in countries and regions previously unfamiliar with such global linkages. With my colleague Zoltán Csányi, I have been exploring by means of statistical macro modelling whether these changes can be linked to emigration decisions. On the basis of data from 63 countries, building on pioneering efforts by Saskia Sassen (2006/1988) and Sanderson Kenton (2009), we have been using linear regression analysis to show that the change of system between 1990-95 contributed to a rise in emigration some years later.

Initial results suggest that the rise of foreign direct investment does indeed play a role in the rise of emigration from some societies, though the impact on outmigration follows with a lengthy lag of 10-15 years. Our research has pinpointed the decisive co-variables: migration path dependency, the decline of agricultural labor, and changes in the relative income levels of countries and regions. Our modelling provides no support for notions of unilinear development (migration transition) as proposed by modernization theory. Marketization does not lead mechanistically to rising emigration. It is necessary to examine the opening up of national economies in the globalization process with reference to the specific interplay between the above variables.

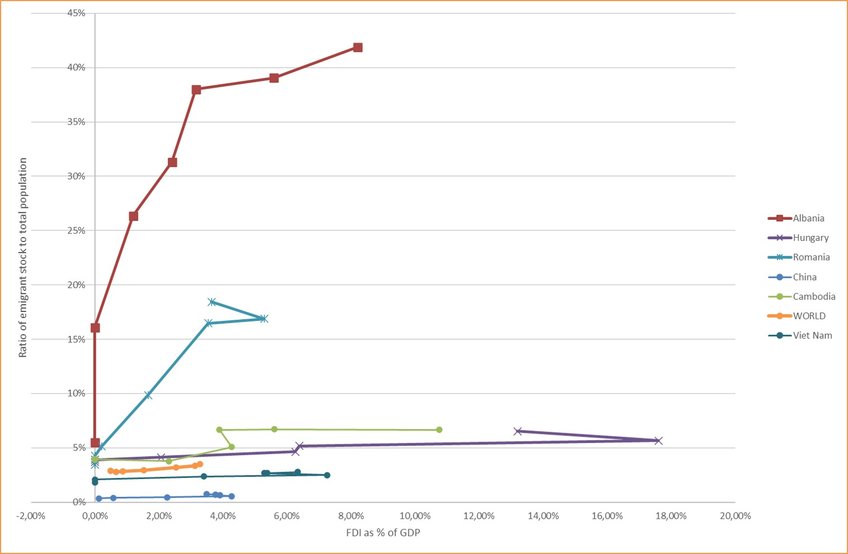

Even within countries that have experienced socialism in one form or another, “developmental routes” differ greatly. The graph below shows how emigration rates (the stock of those who were born in the analyzed country but lived somewhere else as related to the total population) have changed between the years 1990 and 2019 (y axis) relative to net inflow of Foreign Direct Investment as a percentage of total GDP 10 years earlier (x axis). (This decade is introduced to take account of the lag we found in our modelling.) None of these countries enjoyed a significant inflow of foreign investment in 1990, though some East European countries were already above the global average in their emigration statistics.

With both axes changing value significantly, a straight line suggests a strong link between FDI and emigration 10 years later. If we look at the different paths of development and we include the related processes of declining agricultural employment and relative income positions (not represented in the graph) then some interesting results emerge.

Vietnam has shown high growth rates and a dynamic opening up to foreign capital without becoming an emigrant society. Emigration levels have just increased from 1,82% in 1990 to 2.5% in 2019. This is perhaps due largely to the fact that the decline in rural employment (from 71% to 37%) could be absorbed by other sectors of the economy. Similar things happened in China, where international emigration rates have just increased from 0,35% to 0,54%, while the rate of FDI has increased substantially (to 4.3% of GDP) and rural employment has fallen massively from 60% to 29%. Both countries have been able to increase their relative income positions, China from 12% of the global average of GDP per capita to 87%, and Vietnam from 8% to 23%. This dramatic improvement in incomes might well have contributed to rising emigration levels (because we know that increasing income increases migration capabilities). Yet this did not happen. Vietnam and China thus demonstrate that economies which remain nominally socialist can transform their labour markets and open up to FDI without there being a surge in international emigration.

Cambodia is another interesting case. This country has opened up its economy to foreign capital in a regionally unprecedented way (to a level above 10%) and there was a dramatic decline in rural employment rates from 79% to 32%. Meanwhile the average income level increased from 5 to 13% of the global average, and emigration almost doubled (from 3.9% to 6.6%). In Eastern Europe, Hungary exhibits similar FDI rates, but relatively low rural employment (a decline from 12% to 5%) and only a small improvement in relative income (from 128% of the global average to 134% in 2019). Both countries are well above the global average for out-migration, due to higher starting levels as well as to the subsequent opening up.

Albania and Romania obviously belong in another world, well above global levels both in terms of the penetration of capital and emigration. These states opened up their economies in the early 1990s, when the rural sector was still substantial. In some regions agricultural employment increased due to the so-called transformation crisis: urban labour markets disintegrated when transnational corporations moved and swathes of local industry were closed down. These changes led to a massive upsurge in emigration. High rates of migration had nothing to do with joining the EU but started much earlier, despite all the obvious difficulties. If our analysis is correct, many more Albanians and Romanian would have migrated earlier, but they lacked the resources to be able to do so.

The globalization-migration nexus exists and Sassen’s original insights are confirmed in our models: inflows of foreign capital are statistically related to rising outmigration. Our work also confirms that Karl Polanyi is right to see marketization as a cause of disembeddedness, which is exemplified by high levels of mobility of the “fictitious commodity” called labour. But it is important to recognize that these relationships are far from mechanistic, since other variables must always be taken into account. It is also necessary to find ways to measure the shock and anxiety that accompany the opening up of previously sheltered economies, and how this emotional context conditions “countermovements”, as observers like Hann (2019) have argued long before the current rise of nationalism.

References

Hann, Chris. 2019. Repatriating Polanyi. Market Society in the Visegrád States. Budapest: Central European University Press.

Sanderson, Matthew R. and Jeffrey D. Kentor. 2009. Globalization, Development and International Migration: A Cross-National Analysis of Less-Developed Countries, 1970-2000 Social Forces, 88 (1): 301-336.

Sassen, Saskia [1988] 2006. Foreign investment: a neglected variable. In Anthony M. Messina and Gallya Lahav (eds.): The Migration Reader. Exploring Politics and Policies. London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, pp. 596–608.