The dangerous guest: Exploring everyday uncertainty in the year of COVID-19

Authors: Nina Nissen, Ingrid Charlotte Andersen, Charlotte Simonÿ

Illness narratives are central to how people experience, understand and manage their illness, treatment and recovery in everyday life. Health professionals find such narratives relevant to gain insights into their patients’ daily lives with illness. However, reflecting on her experience with COVID-19, Callard (2020) notes: ‘there are no narrative anchors yet in place’ that recognise the lived experience of COVID-19 infection and its sometimes long aftermath. Aiming to provide such anchors, this study-in-progress explores the illness experiences of people diagnosed with and possibly treated for COVID 19, and examines their ways of managing their recovery in everyday life.1

The illness narratives and stories of recovery shared by our participants highlight the lived experience of profound and multi-faceted uncertainties, whereby the body is central, both in terms of the expression of symptoms and as the focus of daily activities in managing needs and priorities for recovery and practices of care. Uncertainty is frequently an integral experience for people living with chronic illness, forcing ill people to adapt repeatedly as they experience bodily and/or emotional changes. Exploring the many facets of uncertainty associated with the experience of COVID-19 infection, we draw on Warren and Ayton’s (2018: 142) concept of phenomenological uncertainty, which they define as ‘the sense of uncertainty pervading everyday lived experience’. This highlights the variations of subjective (phenomenological) experience of illness between individuals as well as the fluctuations that occur within an individual’s illness experience over time. Our focus here is on the latter.

Illness narratives are intensely personal; but they are also deeply shaped by structural, relational, and cultural dimensions and social contexts. The story we explore below derives from an interview conducted at the beginning of the summer, approximately three months after our participant’s diagnosis and subsequent seven-day hospitalisation in spring 2020. The interview took place at a time when pandemic restrictions in Denmark were being gradually lifted and everyday life was regaining a sense of normality. Public health recommendations were becoming part of familiar routines, most noticeably the ubiquitous hand sanitiser dispensers in public and semi-public spaces. Hope that the Coronavirus would soon be a problem of the past, at least in Denmark, was palpable during those summer months. Yet, earlier in the spring, Anglophone media had reported harrowing stories of devastating long-term effects following even supposedly mild cases of COVID-19 infection. The term ‘long-hauler’ was coined by people with prolonged recovery times and a now global group of COVID-19 patient-researcher activists2 completed its first survey of long-hauler experiences (Assaf et al., 2020). By the end of the summer, long-hauler stories were being published in Danish media, and a Danish-language Facebook group had been formed by people suffering long-term symptoms. Meanwhile the term ‘long-COVID’ became ubiquitous in the British Medical Journal. Thus, this interview took place - and indeed our study started out – in the context of tensions between a return to normality and the realisation that diffuse and unpredictable suffering was continuing to shape some people’s everyday lives. The account presented here was chosen for its representative character in illustrating the profound uncertainties shaping illness experiences with COVID-19.

Merete’s story

Merete, in her late 40s/early 50s, is a mother of three young adults, married, living in a rural area near her place of work where she is a health professional. She suspects that she was infected while treating a patient. Merete describes herself as having previously (before the infection) been healthy, active and very sporty; for example, she is a keen sportswoman and she and her family would go for long walks with the family’s two dogs, which now, like her husband, often have to wait until she catches her breath again to walk a little further (see Figure 1). At the time of the interview, Merete’s struggles with the prolonged physical, cognitive and emotional effects of COVID-19 infection and her determination to regain her health dominate her everyday life. She is back at work part-time despite not having fully recovered; she feels she wanted and needed to return to work, even though it comes at the expense of not having a social life, as she has no energy to spare.

Merete finds it physically, affectively and mentally challenging to manifest symptoms of a new disease, particularly as the course of the infection appears random. Her husband and one of her children were diagnosed with COVID-19 after her own diagnosis, yet they experienced different symptoms, recovered at different rates, and noted no after-effects. Thus, she says, COVID-19 is ‘a disease with many faces’. Not knowing how the course of illness, treatment or recovery might unfold proves intensely disturbing, ‘enormously hard’ and a ‘psychological burden’. Though Merete no longer suffers panic attacks with out-of-control breathing, she still experiences severe respiratory problems, cognitive impairments and intense tiredness, all of which she describes as profoundly challenging. Of her tiredness, she says, she is ‘tired of being tired’.

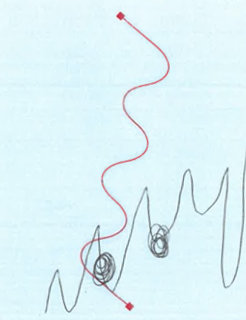

To explain her more acute illness experience around the time of her diagnosis, hospitalisation and the first weeks after being discharged from hospital Merete draws an upward moving zig-zag line with uneven troughs and spikes, punctuated by ‘knots’ (see Figure 2, black line; the red line derives from a researcher-produced visual prompt used during the interview). This visualisation reflects both unpredictable symptom fluctuations and the steady worsening of symptoms, including a wider range. The ‘knots’ indicate periods with panic attacks due to a fear of not being able to control her breathing and intermittent feelings of being overwhelmed by a terrifying sense of never recovering.

Fluctuations continue to characterise her ongoing recovery, which Merete experiences as ‘terribly slow’ with ‘two steps forward and sometimes three steps back’. The tempo of progress makes her feel sad and frustrated, as ‘one doesn’t know when [things will be better] because there isn’t anyone who has any experience with it. So, I don’t know. I cannot look forward.’ This lack of knowledge she finds ‘deeply frustrating’. What one needs, she observes, is for someone ‘to hold your hand’ and ‘say “you need to do this and that”’ in order to get better, a point she reiterates during a later casual conversation. Merete confides that she has at times wondered whether it’s ‘just me’ or ‘in my head’ or that she is ‘imagining things’. Not that she really doubts her perception and bodily self-knowledge, but, she says, it is very hard to grasp that ‘the body suddenly stops functioning properly’ and ‘one simply does not know oneself’.

While struggling with the unpredictable and slow progress of recovery, professionals’ and her own lack of knowledge about how to support her recovery or even explain her current symptoms, Merete also worries that she might pose a danger to others. In her address to the nation on March 17, 2020, Queen Margrethe of Denmark described the coronavirus as a ‘dangerous guest’. This metaphor lingers. Merete recounts that people step back from her when they hear that she has had COVID-19, apparently considering her to be dangerous. Nor does she actually know whether she continues to be a danger to others, such as her elderly parents. To avoid any potential risk, the extended family follows guidelines on physical distancing by meeting outdoors only and the older generation is no longer greeted with a hug.

Although Merete’s illness experience up to now is dominated by deep uncertainties, she hopes that upcoming biomedical investigations will ‘tell her something’, for instance clarify reasons for some of her current respiratory symptoms. This hope, she says, keeps her going right now and then she will take things from there. A few weeks later, during a brief chance meeting, she mentions that she is slowly getting better. She has obviously thought a lot about her experience with this new, unknown and ‘dangerous guest’, and emphasises that doctors should ask about and explore the things they don’t know. How else, she says, would they find out what is going on and how to help?

The lived experience of uncertainty

This story reveals multiple experiences and sites of uncertainty. Crucially, Merete found it challenging to manifest symptoms of a new disease without knowing how the course of illness, treatment or recovery might unfold. A lack of understanding about COVID-19 contributes towards people with COVID-19 symptoms, like Merete, doubting their symptoms to be real, health professionals (and others such as family members) questioning reported symptoms or attributing symptoms to anxiety (e.g. Assaf et al., 2020). This lack of knowledge and unpredictability foreshadow unknown and frightening futures for self and others. The close association of the coronavirus with danger, risk and uncertainty compounds such imagined futures and reveals the double meaning inherent in the metaphor of the dangerous guest, while also shaping care practices for self and others. These implicate familiar or newly familiar bodily routines, from (not) shaking hands, (not) hugging relatives and friends to remembering to disinfect hands before entering a shop or office. Also, requirements of physical distancing and the restriction of social contacts alter practices of conveying affect and of sociality. This has led to concerns among some people about the possible lack of Xmas hygge for which extended family gatherings are essential.

In contrast to the current treatment of COVID-19 infection and possible late sequelae, many chronic diseases are managed by standardised, evidence-based treatments and care pathways. On October 30, in recognition of the frequency and severity of late sequelae reported by some of the 44.000 people with confirmed COVID-19 infection, the Danish Health Authority released recommendations for the establishment of specialised clinics and associated care pathways for those with COVID-19 late-effects (senfølger)3, a term apparently borrowed from cancer treatment and its often long-lasting side-effects. The recommendations are described as a first step in developing care plans for people experiencing prolonged symptoms and are expected to be updated as new knowledge emerges. Thus, they recognise the uncertain and fluid character of knowledge about the pandemic and any local or global healthcare responses but also demonstrate biomedicine’s approach to managing uncertainty through standardised routines, however temporary.

People living with chronic illness tend to be familiar with standardised care packages (pakke forløb) and these kinds of ‘narratives’ may be perceived as professionals’ ‘holding my hand’ and knowing what to do, as longed for by Merete. In the case of COVID-19, these and other ‘narrative anchors’ (Callard, 2020) that reflect the multi-faceted experiences of affected people highlight the significance of illness narratives in the everyday lives of the sick, and for healthcare provision. Illness narratives are intensely personal. One person’s story can reveal, as we have illustrated, multiple uncertainties pervading everyday lived experience, together with wider social and political implications. In speaking truth to power, illness narratives also have a profound force, moving, for example, medical institutions and health systems such as the British Medical Journal and the Danish Health Authority to acknowledge and address urgent, albeit new and uncertain, long-COVID needs. However, uncertainties are likely to remain and approaches be contested. There are indications that individuals’ experience of COVID-19 symptoms differ considerably from the categorisation of COVID-19 infections as asymptomatic/mild, severe and critical (World Health Organisation, 2020) and debates about the diagnosis of long-COVID abound. The dangerous guest continues to linger. The summer is over.

Notes

1 Given the ongoing constraints on ethnographic fieldwork, we predominantly draw on the rich interplay between verbal and visual narratives based on in-depth interviews and the use of participant-produced images and other visual prompts; fieldwork will be carried out if/when possible.

2 See https://patientresearchcovid19.com/

3 See https://www.sst.dk/da/Udgivelser/2020/Senfoelger-efter-COVID-19

References

Assaf, G., Davis, H., McCorkell, L., Wei, H., O’Neil Brooke, Akrami, A., . . . Adetutu A. (2020). What Does COVID-19 Recovery Actually Look Like? An Analysis of the Prolonged COVID-19 Symptoms Survey. Retrieved from https://patientresearchcovid19.com/research/report-1/

Callard, F. (2020). Very, very mild: Covid-19 symptoms and illness classification. Retrieved from http://somatosphere.net/2020/mild-covid.html/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+Somatosphere+%28 Somatosphere%29

Warren, N., & Ayton, D. (2018). (Re)negotiating normal every day: Phenomenological uncertainty in Parkinson’s disease. In G. M. Gareth M. Thomas & D. Sakellariou (Eds.), Disability, Normalcy, and the Everyday (pp. 142-157). Abingdon: Routledge.

World Health Organisation. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report 46. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200306-sitrep-46-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn= 96b04adf_4