Conflicting political identities in northern Somalia

In the Somali civil war the state collapsed in the early 1990s. Up to now every attempt to rebuild it again failed. This, among a legion of other problems, led to a crisis of the political identity of many Somali. The question is: Where shall people orientate with regard to the state?

During 15 months of fieldwork in northern Somalia it emerged that the issue of political identity is connected to a crisis of national identity. With Somaliland in northwestern Somalia and Puntland in northeastern Somalia two de facto-states have been set up which partly fill the state vacuum.

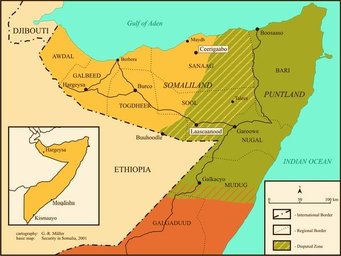

In the last 14 years a remarkable level of peace and political order has been attained here. But between 2002 and 2004 this achievement has been questioned by several serious escalations of political and military conflicts between Somaliland and Puntland. These conflicts resulted from incompatible positions regarding the self understanding and the political future of both de facto-states and their populations. Somaliland is presented by its government in Hargeysa as independent state which in 1991 seceded from the rest of Somalia in the borders of the former British Protectorate comprising different clan-families and clans.1 It claims international recognition on grounds of territoriality complemented by a notion of a Somaliland national identity. Puntland was established in 1998. According to its constitution it is a part of the Somali state and works for the rebuilding of a unitary Somali government. Its government in Garowe is based on an alliance of different Daarood/Harti clans. Apart from this genealogical identity the Somali national identity is adhered to.

In northern Somalia the propaganda issued in the political centres but also discussions about and manifestations of political identity in daily life reflect the tensions between the Somaliland- and the Darood/Harti- respectively Somali identity. Both administrations claim the regions Sool and Sanaag as well as the city of Buuhoodle and its surroundings (see map) as their state-territory. The reasoning of Hargeysa is that the named territories were part of the British Protectorate of Somaliland which unified in 1960 with the Italian administered Somalilands to form the Republic of Somalia. Garowe argues that they are predominantly inhabited by Harti-clans belonging to the Darood-clan-family. For obvious reasons the tensions between both administrations escalated in the time around the election of the former President of Puntland as new Somali President at the end of the Somali peace and reconciliation conference held in Kenya 2002-2004.2 This research-project focuses on the logic of political identification of individuals and groups in the context of re-emerging state structures in northern Somalia and how these identifications are related to conflict especially in the politically contested regions Sool and Sanaag, as well as the town of Buuhoodle.

I argue that as a result of the civil war and the following developments in the study area new identities formed on the ground. These identities are not ethnic identities in the sense that anyone in or outside northern Somalia would seriously argue that the carriers of these identities would belong to different ethnic groups. They rather can be understood as political identities which are based on features resembling ethnic identities such as descent, history, individual experiences and collective memory. These identities are also significantly connected with certain territories because the land in northern Somalia is divided between descent-groups. These identities are not new in the sense that they are invented from the scratch. But they combine existing identity markers in a particular way and are meaningful in the current political context of the area.

Flexibility comes in because for each identity certain aspects of history, clan-relations and culture are highlighted, others are completely neglected. This allows individuals to manoeuvre to a certain extent when it serves their interests. It also causes contradictions when it comes to individual life histories and to the experiences of different generations. The identities under discussion are internally fragmented. Nevertheless, when the question of the political future of Somaliland and Somalia is at stake, the relevance of these internal fragmentations diminishes and the identities form relatively clear blocks which divide the social, political and territorial landscape of northern Somalia today.

1I.M. Lewis (A Pastoral Democracy, Oxford, 1961) described the Northern Somali society as based on a segmentary lineage system, in which individuals take their position according to their (sometimes fictive) patrilinear descent. Lewis differentiates groups according to the levels of segmentation (from top to down) as “clan-families”, “clans”, “sub-clans” and “diya-paying groups”.

2Members of the new administration moved to Somalia recently. However, due to tensions inside the government and in southern Somalia effective administrative work did not yet start.