Conflict, violence and integration: Transnational and local fields of governance on the Chad/ Sudan border

This project on integration strategies of refugees in Dar Masalit has acquired new relevance through the recent escalation of violent conflict in Darfur, Western Sudan. The causes of this escalation cannot be understood along simple lines of explanation. Religious differences, as a factor for conflict, fall aside, since the whole population of the region has long been Muslim. What is more, the strains between sedentary farmers and nomadic herders, proposed by the Sudanese government as a source of the conflict, are unlikely by themselves to have led to this extreme kind of escalation. On the side of the local population and the rebels in Darfur, it is believed that the Sudanese government under president Al-Bashir (and his predecessors) is responsible for the recent conflict. From this point of view, the government has neglected to include all regions of the country in sharing the power and wealth. Relating to these different ways of explaining the conflict, a central thread of analysis in this project concerns patterns of identification and belonging among the people affected by the conflict. Along which lines do individuals and groups define themselves? Why does someone belong to this or the other or yet another side in the conflict? Which historical, political, religious and other identities are instrumentalised or internalised by the actors? These questions point to a historical component about how belonging, alliances and oppositions were negotiated in the past and today. They also point to the national and international level, to the influence of different governments, how they manifested themselves on the international border and, thereby, changed the region.

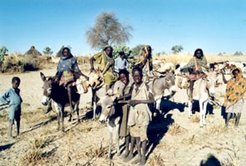

Dar Masalit (“Land of the Masalit”), the border region between Chad and the Sudan where the research took place, is of particular importance in this context. The region serves as a centrally located conduit linking these countries. On the Sudanese side the organisers of several military putsches in Chad took refuge in the past. In this same area, during the 1980s Muammar al-Qaddafi armed supporters of his policy of Arabisation from Libya against his adversary, the former Chadian dictator, Hissein Habré and against Habré’s ally Jaa’far al-Nimeiri, the former president of Sudan. As a result, weapons are still abundant in the region, and the escalation of even minor conflicts is an ever-present danger. All changes on the level of central governments in the two neighbouring states have an immediate impact on the border region: thus, the fall out between today’s Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir and his former mentor and powerful Islamist leader, Hassan al-Turabi, in 1999 caused massive changes in the political landscape of Darfur, which then came to be one of the causes of the 2003 rebellion. On the other hand do the events in the border region affect the central level: the failed coup d’état against the Chadian president Idriss Déby in May 2004 is interpreted as a direct result of his failure to support the Zaghawa, his ethnic group of origin, who are among those bashed by the fighting in Darfur.

But the border itself also has acquired new importance as a possible point of transit for potential refugees moving in both directions. Today, the refugee camps along the border in Chad seem to be well supplied by international aid agencies and fairly secure from attacks by the Sudanese government and mounted militia. The exact opposite was true in the early 1980s during the Habré dictatorship in Chad and above all during the famine in 1983/84. At that time, the aid agencies were in Sudan, and crossing the border in that direction promised a safe haven from murdering and plundering soldiers in Chad or from starvation. Thus, interactions among local actors and transnational linkages, including their respective influences on fields of governance, are the two central issues of this research project.

In the perspective developed in this project, political engagement and influence does not originate primarily from the state or government. Instead, the role of local actors or groups of actors is emphasised. In their interaction, all participating actors contribute to fields of governance, which through changing channels of material distribution and the introduction of new categories of rights and entitlements have variable effects on different parts of the population. Governance relationships, the possibilities of their maintenance, and the processes of their transformation thus shift to the centre of analysis. Of importance are also mutual influence as well as the manipulation and redefinition of local discourses of meaning. In its presence or absence, the state influences different parts of society differently, especially in terms of access to state support for some groups at the expense of others. The same is true for international organisations, which influence local conditions with or without the help of the state. The analysis of the different levels on which local, national, and international actors make decisions thus reveals a complex web of relationships that result from the intended and unintended consequences of these very interactions.