High Default Rates and High Trust: A Moral Dilemma for the Owners of Small Businesses in China

Author: Lizhou Hao

August 19, 2016

A recent study on Days Sales Outstanding (DSO) by Euler Hermes shows that in 2016 firms in China have to wait on average 92 days to get paid. It is as much as 134 days in the machinery and equipment industry. This is the longest time worldwide.1 The Chinese media have picked up on this as a news item, but in my field site, Shishi, the habit of delaying payment stretches back decades. Chatting with businessmen who do business across the country, I was surprised to learn that Shishi exemplified the widespread prevalence of default and high trust. Defaulting – locally to describe someone who fails to pay back a debt or to settle the invoice of a supplier on time – poses a moral dilemma for the majority of the proprietors of small businesses I have surveyed.

The past 30 years of economic reform and opening up witnessed the development of Shishi from a group of villages to a modern city. Nevertheless, the ongoing rapid urbanization has not completely faded out the colour of rural economy and the morality of local peasants. In contrast with China’s nearly 900m2 arable land per capita, Shishi’s per capita arable land is, by my rough calculations, just around 90m2. Unlike subsistence security, which has been emphasized by Scott (1976) as being a base moral value among peasants, changing cultivation techniques to increase yield under the safety-first principle has never become a popular option for peasants in my field site. Due to the shortage of cultivated land, these peasants have to make a living by doing business instead. Especially for the first generation that started family firms in the 1980s, their motivation for engaging in risk-taking and sometimes illegal trades was simply survival. It is a feeling of ‘having nothing to lose’ that gives local people great courage to get into long-term debt and foxy wisdom to operate an eighty-thousand-euro business with only ten thousand euros cash flow in account.

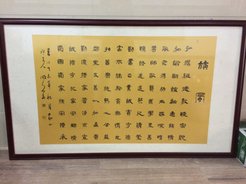

People in Shishi worship ancestors in their own family temples on some special days. The family temple is a symbol of Confucian filial piety on the one hand, and an effective way of organising family members so as to utilize their human, material and financial resources on the other. Small businesses are often first set up by borrowing money from family members who trust the ability of the debtor to repay in a short term. But when a large sum is needed and there are insufficient creditors, and worries exist about the strict conditions of bank loans, these new entrepreneurs tend to look for some informal fund raising platforms.

Biaohui, a sort of rotating savings and credit association (ROSCA) established by relatives and friends regularly putting certain amount of money together into a pool in case of anyone’s need within this group, once was very popular and aroused interest among anthropologists, such as Fei (1939, p. 267). Usually an old man in the big family or an important person the village plays a role as a supervisor of this mechanism for collective saving and lending. There is no contract in this sort of financial aid society. However, the Confucian virtue of being honest and trustworthy can always be found in the moral rules of different families. Relying on blood and regional relationships, people trust each other and don’t in practice worry much about the exact time of repayment. To some extent, it is too much interpersonal trust and informal management of loans that result in the high tolerance of default in many business circles. But not until in recent years have people begun to consider Biaohui unreliable, risky and illegal, because many promoters took a large amount of money from the pool and ran away when they faced a tough time in local economy.

High levels of indebtedness have become familiar to the clothing industry, not only in Shishi but nationwide and even worldwide. Lots of foreigners come and join the game of delaying payment with local businessmen. One of my informants closed his garment factory this summer and flew to Poland to pursue a Polish debtor. Chains of debts link many firms. The majority of small family businessmen I have interviewed are currently owed between 40.000 and 300.000 euros.

Many of them, of course, have dual roles as both creditor and debtor. After complaining about - in their words - the local ‘culture of debt’, they express a feeling of helpless and articulate a moral dilemma: ‘I do not want to default. What matters is that I’ve promised to pay my debt sooner or later. I’m trying to do that little by little, but it takes time. I can only transfer the money to my upstream firms after I get my debt paid by downstream firms. If I force a downstream firm to pay off the debt by law now, it probably will go bankrupt, which is likely to impact my industry chain, and I’ll lose more than I gain.’ It is immoral to leave one’s debt outstanding, but one does not deny the moral commitment to pay off the debt eventually. A creditor of course legitimately has the right to recover what is owed to him, but is it ethically defensible to destroy a long-term partnership with a small firm? In a nutshell, to accept and adapt to the prevailing debt default phenomenon is the morally pragmatic solution for both sides. Only when a debtor disappears will the creditor sue him.

As the Chinese saying puts it, harmony brings wealth. Facing the outstanding payment, businessmen in China show average 92-day tolerance and even a Confucian benevolence to debt defaulters for the sake of sustainable development of industry chain, stable cooperation and profit in the long run. Graeber (2011, p. 242) points out that Confucian ideal of benevolence is basically just an inversion of profit-seeking calculation. In other words, what under the surface of moral issues of high default rates and high trust is the evaluation of overall interest which people are embarrassed to highlight in Confucian culture. In interpersonal relationships, like mutual trust and kindness, Confucian thoughts still have subtle influence on businessmen. Although Chinese firms are suffering the moral dilemma of debt default, it is still good to find that, in terms of social trust, 60.3% of those mainland Chinese people surveyed believe ‘most people can be trusted’, which ranks second out of 61 countries and regions in the World Values Survey 2014.2

References

1http://www.eulerhermes.com/mediacenter/Lists/mediacenter-documents/Economic-Insight-Worldwide-DSO-Paying-the-Price-for-Low-Growth-July2016.pdf

Scott, J. C. (1976). The moral economy of the peasant: rebellion and subsistence in Southeast Asia. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Fei, X. (1939). Peasant life in China: a field study of country life in the Yangtze Valley. London: Routledge.

Graeber, D. (2011). Debt: The first five thousand years. New York: Melville House Publishing.

2http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSOnline.jsp