The use of Twitter by and for African migrants in crisis

Tebit Hilary Tita

Shock (Im)mobilities Special Section: African Migrants in the Ukraine War

Curated by Mengnjo Tardzenyuy Thomas

Tita, Tebit Hilary. 2023. The use of Twitter by and for African migrants in crisis. MoLab Inventory of Mobilities and Socioeconomic Changes. Department ‘Anthropology of Economic Experimentation’. Halle/Saale: Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology. https://doi.org/10.48509/MoLab.7495

Download as PDF

The role of social media in publicising the plight of African migrants displaced in Ukraine following Russia’s military invasion on the 24 February 2022[1] should not be underestimated. Many people followed, and still continue to follow updates about the invasion through social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook and weblogs. Aside from reporting on the tribulations of African migrants, social media has also been used to contact and trace migrants displaced by the conflict. Faced with displacement and compounded by discriminatory practices against Black and African migrants reported along Ukrainian borders,[2] many people – including migrants themselves – turned to social media to contact and trace friends, family members, compatriots and loved ones. This entry seeks to shed light on the various ways in which social media platforms, and particularly Twitter, the most important platform in this regard, have been used to contact and trace African migrants displaced by the war in Ukraine.[3]

The establishment of the Pan-African Twitter account @AfricansinUkraine

In March 2022, African migrants created a new Twitter account Africans in Ukraine[4]. The account was used to share information about the registration of Nigerians wishing to be evacuated from Ukraine. Its tweet dated 9 March 2022 stated that “Registration for the evacuation of Nigerians arriving from Ukraine is ongoing” and it provided a link to a registration form.[5]

Twitter has been used as a platform for sharing and tracking the mobility of African migrants in Ukraine. A wide audience around the globe follows updates on the mobility of migrants trapped by the conflict. For instance, on 8 March 2022, Africans in Ukraine tweeted that “[w]e are following the stories concerning the evacuation of Sumy students. We are waiting to hear their arrival at the borders & beyond.”[6] In this way, stories of African migrants trapped en route were given immense social media attention, attracting the attention of public authorities and well-wishers who had the means to help. Lukwesa Burak, a Zimbabwean journalist who works for BBC News, tweeted how African migrants like medical student Ellen were stranded in Sumy (figure 1).

Some Twitter users sought accommodation from good Samaritans willing to house or shelter displaced Africans. Some of these tweets found responses. For instance, in a tweet with the hashtag #AfricansinUkraine, Shinyfluff, a co-founder of Artists for Black Lives Matter, requested accommodation for a night for a Nigerian student in Budapest about to transit to Poland (figure 2)[7].

The tweet was successful, with Shinyfluff adding later that the day that “the housing situation is resolved‼”[8]

Other specific functions of social media

Aside from Pan-African twitter channels like Africans in Ukraine, governments and other social activists also used Twitter to reach out to migrants, to make contact with others, to form groups, and to provide real-time information about exit routes. African governments used Twitter to identify and contact nationals trapped in Ukraine for eventual evacuation. At the time, Twitter was considered the fastest and simplest means of conveying and sharing information to a wide audience. In a tweet dated 10 March 2022, the Nigerian Embassy in Budapest[9] wrote that registration for the evacuation of Nigerians arriving from Ukraine was ongoing, and those concerned were directed to fill out the attached form.[10] The form asked if migrants had a passport and other travel documents, if they were willing to be evacuated to Nigeria, if they needed any form of assistance, and where they would stay in Hungary.[11] This particular tweet was a success, leading to the evacuation of a number of migrants: “Transportation of the 1st batch of 174 evacuees to the Budapest International airport for evacuation to Nigeria is underway. Another aircraft is expected to airlift more Nigerians back home.”[12]

Twitter was also used to publicise the safest routes to flee to neighbouring countries. The President of the Nigerian Diaspora Community in Poland, Dr. Trade D. Omotosho,[13] made a number of tweets advising Nigerian migrants wishing to flee to Poland on which borders to cross, and where they were to stop (figure 3, figure 4).

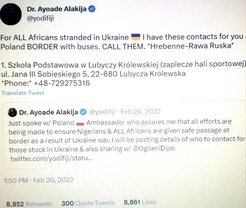

Twitter was also used by social media influencers and activists to provide stranded African migrants with telephone numbers they could use in order to be ferried from Ukraine. Nigerian social activist and barrister Dr. Ayoade Alakija[14] tweeted a phone number for Africans stranded at the Polish border to call for buses to evacuate them from Ukraine (figure 5).

Social media also serves as an active platform for African publics from different countries to participate in debates about global geopolitics and the role of Africa in the war. Most social media debate focused on the alleged ill treatment of African migrants at Ukrainian borders. The Nigerian President’s Office issued a statement on its Twitter account: “There have been unfortunate reports of Ukrainian police & security personnel refusing to allow Nigerians to board buses and trains heading towards [the] Ukraine-Poland border … [w]e understand the pain [and] fear that is confronting all people who find themselves in this terrifying place … [w]e also appreciate that those in official positions in security and border management will in most cases be experiencing impossible expectations in a situation they never expected … [b]ut, for that reason, it is paramount that everyone is treated with dignity and without favour. All who flee a conflict situation have the same right to safe passage under UN Convention and the colour of their passport or their skin should make no difference …”[15] In a tweet entitled “Statement of the African Union on the reported ill treatment of Africans trying to leave #Ukraine”[16], the African Union (AU) also expressed its disquiet about alleged racial discrimination against Blacks and Africans in Ukraine.

The preceding examples show that Twitter as a social media platform was not only instrumental in the contact tracing of African migrants, but also in publicising the plight of African migrants. It was used by social activists, African governments and other bodies to identify and register migrants, to provide information on the safest routes, to provide emergency contact numbers at the border, to monitor migration, and to find accommodation for the displaced.

[1] Parker, Claire. 2022. What counts as an 'invasion,' or as 'lethal aid'? Here's what some terms from the Russia-Ukraine crisis really mean. The Washington Post. 23 February 2022. https://archive.today/2022.02.23- 204700/https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/02/23/key-terms-russia-ukraine/. Last accessed 29 November 2022.

[2] Tardzenyuy Thomas, Mengnjo. 2022. Shock (im)mobility: African migrants and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. MoLab Inventory of Mobilities and Socioeconomic Changes. Department ‘Anthropology of Economic Experimentation’. Halle/Saale: Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology. https://www.eth.mpg.de/molab-inventory/shock-immobilities/shock-immobility-African-migrants-and-the-Russian-invasion-of-Ukraine. Last accessed 28 November 2022.

[3] We take contact-tracing to refer to the means of identifying African migrants displaced by the war.

[4] Twitter account Africans in Ukraine at the address @BringOurPPLhome. Available online at: https://twitter.com/BringOurPPLhome. Last accessed 21 November 2022.

[5] https://twitter.com/BringOurPPLhome. Last accessed 21 November 2022.

[6] https://twitter.com/hashtag/bringourpeoplehome?src=hashtag_click. Last accessed 21 November 2022.

[7] https://twitter.com/ShinyFluffdnd. Last accessed 11 October 2022.

[8] Ibid.

[9] https://twitter.com/nigemb_budapest. Last accessed 21 November 2022.

[10] https://twitter.com/nigemb_budapest/status/1501794709936685058/photo/1. Last accessed 21 November 2022.

[11] https://twitter.com/nigemb_budapest/status/1501794709936685058/photo/1. Last accessed 21 November 2022. The Embassy of Nigeria, Budapest Hungary Assistance Form. https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSddjM-wk88TdJsdOMnXHcmnD1yL29NgJIuCgzP0NoJrFEvuLw/viewform. Last accessed 21 November 2022.

[12] The Embassy of Nigeria, Budapest Hungary Assistance Form. https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSddjM-wk88TdJsdOMnXHcmnD1yL29NgJIuCgzP0NoJrFEvuLw/viewform. Last accessed 21 November 2022.

[13] https://twitter.com/drTadeOmotosho. Last accessed 21 November 2022.

[14] https://twitter.com/yodifiji. Last accessed 21 November 2022.

[15] https://twitter.com/NGRPresident. Last accessed 11 April 2023.

[16] African Union. 2022. Statement of the African Union on the reported ill treatment of Africans trying to leave Ukraine. Available online at: https://bit.ly/3C0EyTc. Last accessed 11 April 2023; Reposted on twitter, #AfricansinUkraine, https://twitter.com/_AfricanUnion. Last accessed 11 April 2023.

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.